Never mind the “wear and tear” of a catcher. Targeted evidence actually favors Realmuto over the next five years.

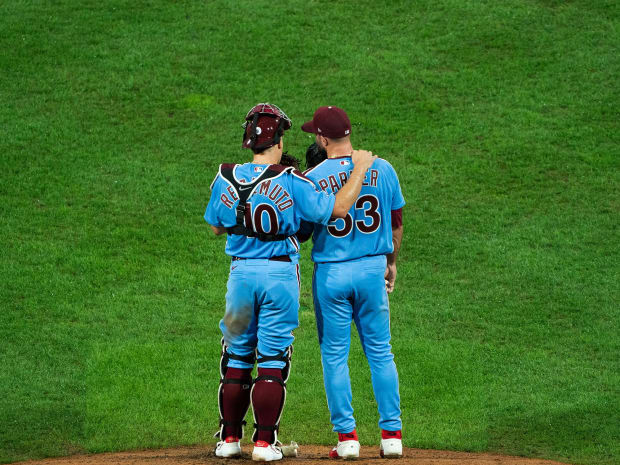

J.T. Realmuto is the best free agent available. As a catcher, he impacts every pitch thrown on the defensive side. He is expert at framing, blocking and throwing. In the batter’s box, he gives his next employer an immediate advantage because catcher is the worst offensive position in baseball. His OPS+ of 116 over the past four years is the best at the position (minimum: 300 games).

Despite these attributes, a narrative has circulated that Realmuto represents a long-term risk because of “the wear and tear” of catching. Critics can point to Joe Mauer, who signed an eight-year, $184 million extension with the Twins in 2010. Four years later, Mauer’s catching days were over because of concussions. His production looked more pedestrian at first base.

Ten years after the Mauer extension, its annual average value of $23 million remains the highest AAV for a catcher. Ten years. Realmuto may finally break through that ceiling. At age 29 (entering his age 30 season), he could get about $118 million over five years. He most likely will sign with the Mets or return to the Phillies, though plenty of other teams will get in on the bidding.

But what about the “wear and tear” narrative? What about all this talk that paying a catcher into his 30s is risky because of the physical demands of the position? Is there a preponderance of evidence, not just folklore, to support this narrative?

No. Targeted evidence actually favors the opposite thinking: that Realmuto will be a good investment over the next five years. Here are five reasons why:

1. His catching odometer is low

Realmuto has caught 663 major league games. That’s not high mileage. That ranks 86th all time through age 29.

He is relatively new to the position. Realmuto was a high school shortstop in Oklahoma who went behind the plate one day when the team’s usual catcher pitched. A Marlins scout happened to be at that game. The Marlins drafted him in the third round with the idea of converting him to catcher.

With the pandemic-shortened season, Realmuto caught only 36 games this year–a respite from his usual grind. Workhorse catcher Salvador Perez, for example, bounced back from his year recovering from Tommy John surgery with his best offensive season.

(One caveat here: Realmuto missed 12 games in September with a hip flexor strain. He played six games upon returning–with no runs and no extra base hits. Teams that review his medicals will have a much better idea of whether there should be any lingering concern there.)

Teams just don’t work catchers as hard as they did a generation ago–or even a decade ago. From 2000-09 teams used their catcher 130 games in a season 31 times. In the next decade, 2010-19, they cut such incidence almost in half, to 18.

2. His best comps tended to be good five-year investments

Compare Realmuto to his most similar catchers. That is, those with the most similar adjusted OPS and games caught at age 29. You get a sample size of eight. Then see how his comps fared over the next five years:

*2 Years

Lucroy and Pagliaroni are cautionary tales. Lucroy was an All-Star at 30, then started to fall off a cliff at 31. Pagliaroni hurt his back and was finished at 31.

But the preponderance of evidence shows that catchers most similar to Realmuto in age, OPS+ and games caught aged well through their early 30s.

3. His athleticism sets him apart

The above list is helpful, but it does not consider one of Realmuto’s greatest strengths: the athleticism of the former high school shortstop. Realmuto is the fastest catcher in baseball, with a sprint speed of 28.2 feet per second.

But to say he is “fast for a catcher” is underrating him. His sprint speed is faster than middle-of-the-diamond players such as Marcus Semien, Jazz Chisholm, Brandon Nimmo, Nick Madrigal and Victor Robles.

Realmuto is an excellent baserunner who takes good secondary leads. He took an extra base 70% of the time this season, far above the league average of 51%. He was on second base five times when a single was hit and scored on those hits four times.

We need even better comps for Realmuto to account for that kind of athleticism. He is one of only eight catchers at age 29 with an OPS+ of 110 and 30 stolen bases (minimum: 500 games). Five are in the Hall of Fame: Carlton Fisk, Johnny Bench, Mickey Cochrane, Gary Carter, Iván Rodríguez.

The comps are even more promising when you look at the select group of catchers that could hit and run like Realmuto. Without exception they remained well above-average hitters. The five Hall of Famers above remained productive and durable through their early 30s. The remaining two catchers are Jack Clements and Thurmon Munson. Clements played from 1884-1900–so long ago as to have seasons cut short by hemorrhoids and typhoid fever, which is to say it has little relevance to today. Munson died in a plane crash during the 1979 season at age 32.

Here is another way to look at Realmuto’s rare combination of hit and run tools. Realmuto has 95 home runs and 44 stolen bases. Only three other catchers reached those thresholds at age 29 and all of them aged well: Bench, Rodriguez and Benito Santiago. Three others just below those thresholds, Cochrane (93, 42), Fisk (114, 40) and Russell Martin (93, 80), also aged well. Do not underestimate athleticism behind the plate when forecasting an aging curve.

4. He can play other positions

From ages 30 through 34 Mike Piazza missed an average of 38 games per year. Unless they were playing an interleague road game, the Mets had nowhere to play him when he needed a break from catching.

Times have changed. The DH is likely to stick around in the National League. Last year Realmuto started 10 games at DH or first base. He is athletic enough to play first base or even left field.

Think about the career arc of Downing. He was an athletic catcher until he broke an ankle at age 30. The Angels then converted him into an outfielder. Over the next six seasons he posted a 128 OPS+ while averaging 147 games a year.

5. Catchers get hurt less often

It sounds counterintuitive, but it’s true. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine did a 10-year study of injuries to catchers and published the findings in 2015 in the American Journal of Sports Medicine. The researchers found “the rate of injuries to catchers is lower than previously reported rates for other player positions.”

The study found that 15% of injuries to catchers occurred from collisions, a risk factor that has been virtually eliminated since the 2013 rule change to prevent them. (The epidemiology was gathered before the rule change.)

History tells us a catcher is almost as likely to play 1,500 games at his position (32 have done so) as a second baseman (35) and a center fielder (34) is at their positions.

We don’t talk about “wear and tear” at other positions as often as we do with catchers. That’s because we can easily see the grinding nature of the catcher’s job: all that gear, the foul balls off the body, the blocking of pitches, the non-stop rivulets of sweat.

When it comes to Realmuto, we have to look past the obvious narrative. When you do, you see a rare combination of skills that suggest some club will make a record five-year investment in him and feel good about it.

——————-