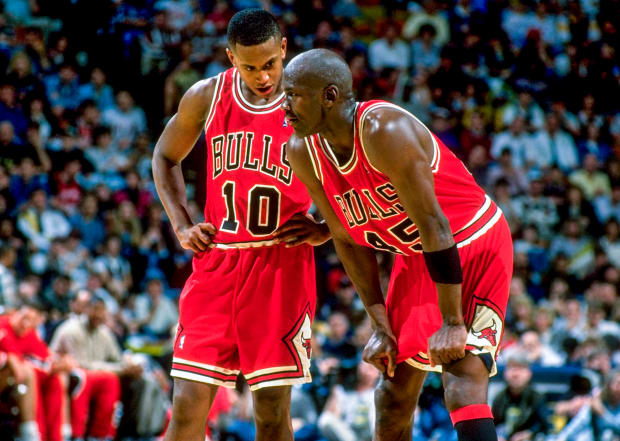

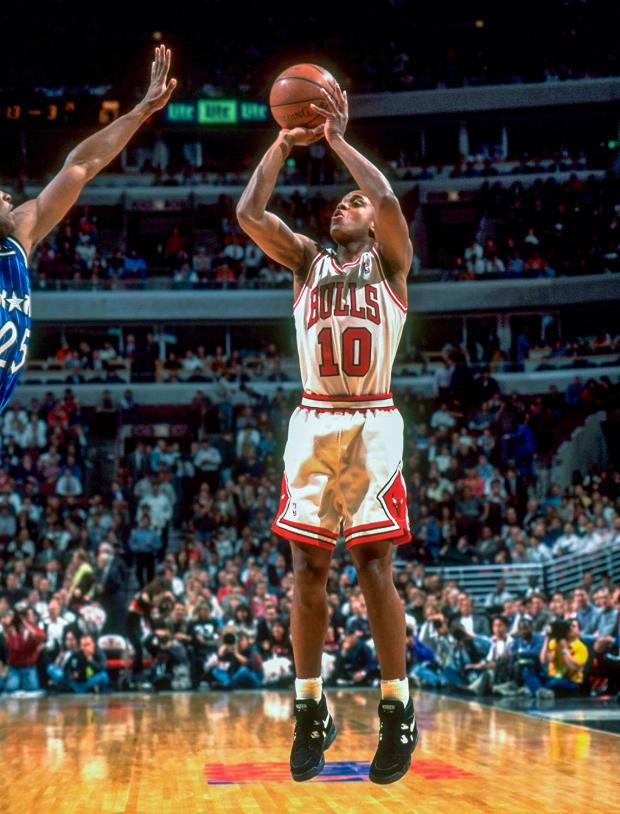

Three-time champ and current agent B.J. Armstrong draws on his NBA career to help players navigate the ever-evolving game.

As a rookie in the NBA, even after an illustrious four years at Iowa, then point guard B.J. Armstrong was getting ready for one of his first road trips as a pro and immediately realized he had some questions.

What am I supposed to pack for a five-game road trip? Armstrong asked himself. I have practice in San Antonio at 8 a.m. tomorrow. What am I supposed to do for the rest of the day?

Early in his pro career, Armstrong learned nobody was going to sit him down and teach him how to manage his time, or answer deceptively complex questions like what he should be doing in the nine hours between practice and tipoff in a city he’s never been to before. Entering the league at 22 years old, Armstrong would be considered ancient for a rookie in today’s NBA. Those memories of confusion from his early playing days led Armstrong to ask himself a question much later in life.

How does somebody who loves the game help those trying to walk a similar path?

***

Since 2006, Armstrong has been an agent as Wasserman Media Group, the high-powered L.A. conglomerate that represents numerous NBA stars. Armstrong had a couple of second shots after his playing career ended in 2000—he was a member of the Bulls’ front office for two years before briefly working as an analyst for ESPN. It wasn’t until he made his way into representation that he found his next calling.

“I’ve always been committed to the game,” Armstrong says. “And I thought, what a unique place it is to watch a kid come in at 19, watch them play until they’re 35 or 36, and to help that young person on their journey. It’s a unique opportunity, and it all stems from the love of the game.”

Armstrong can wax poetic about his passion for basketball, from watching guys succeed on the floor, to helping them make sure they develop their skills, to seeing them grow into people with families who use their stature to impact their communities. You may get the sense that he’s always recruiting, but at the heart of Armstrong’s desire to represent today’s players are the dilemmas that hounded him when he entered the league. If I was having these questions at 22 years old, what’s it like for today’s guys?

In his role as an agent, Armstrong is able to help answer the same questions he had as a rookie. He’s also able to help young players navigate the shifting landscape of the NBA.

The league was much more cut and dried in 1989, according to Armstrong. He was paid to perform a particular service. Teams didn’t ask about his offseason training program; they simply expected him to be ready to go when he showed up for practice. He didn’t have relationships with his coaches outside of the sport. And nobody was focused on his development over a two-to-three-year period. When he got to the Bulls’ front office in 2003, Armstrong was struck by how players entering the league now are presented with a completely different set of problems.

“Today’s athlete is so much more sophisticated,” Armstrong says. “They’re required to adjust much faster. They’re coming at 19 or 20 and thrown into the fire while also constantly evolving with how the game is changing. When I see these kids, I just see myself, and say, ‘Who is helping them to grow?’ ”

There was no light-bulb moment when Armstrong was with the Bulls that made him switch from the front office to the other side of the fence. The three-time champion already intimately knew the challenges that came with playing in the NBA. While working in Chicago, Armstrong was not only exposed to the new problem set for players, he also learned the ins and outs of the business side of the league, gaining insight into negotiations and salary cap machinations. That combination of being both a player and an executive would make Armstrong uniquely qualified to represent athletes.

But nontraditional paths have always raised eyebrows among other agents. In 2008, the same year Armstrong signed Derrick Rose, Michael Jordan’s former agent David Falk accused some players of choosing people close to them to be representatives as a way to pay their friends, as opposed to finding an agent who can best help their interests. The refrain was not new then nor now. Earlier this year, an anonymous agent complained about Klutch Sports and Rich Paul, accusing Paul of simply being an extension of his most famous client, LeBron James. Paul became an agent through an even less traditional path than Armstrong, and his aggressive tactics have raised eyebrows. (The NCAA even tried to pass a rule targeting people like Paul, who represent athletes without a bachelor’s degree. The rule was rescinded almost immediately after heavy criticism.)

Paul, who is Black, has repeatedly pointed out the racial dynamics behind such concerns. When asked about the implications of people being upset with different paths, Armstrong is diplomatic.

“I can see all those perspectives, and I’m experienced enough to know I came into this in a very unusual way,” he says. “I can only speak for myself, and I feel I have a fairly good understanding of this business and the impact it can have on young people. I’ve lived it. I’m not trying to prove anything. I’m not trying to win. I’m humbled to experience what I’ve experienced.”

While Armstrong has been an agent for more than a decade now, at the heart of any thinly veiled criticism directed toward any agent is competition. Armstrong raised eyebrows when he signed Rose—soon to be the No. 1 pick in the 2008 draft—over other highly influential power brokers. A lot of the animosity against Paul stems from the fact that he’s seemingly able to bend teams to the will of his star clients. Most dustups between people in the industry can be chalked up to some form of jealousy. Armstrong tries to stay above the fray, drawing on his previous career to inform his mindset.

“You don’t play in the league and perform at the level I had to being worried about others,” he says. “There’s 20,000 people screaming at me, and I have to make a basket. I don’t know if it’s a gift, but I’ve learned to block stuff out over time. So I’ve never, ever concerned myself with what others are doing. I just do the best job that I can.”

Speaking of the job, it’s more complicated now than ever for practically everybody involved in the NBA. Armstrong is easygoing—he hosts a podcast and was a memorable talking head during The Last Dance documentary. But his demeanor belies the challenges for players as the league looks to start a new season during a pandemic. While the virus remains a threat, the financial ramifications of playing a shortened season without fans will have a direct impact on players’ pockets.

“The biggest challenge is keeping everything in perspective,” Armstrong says. “We are in a pandemic. Being aware of the people around you, being aware of the community that you live in, being aware of the problems around you. I love basketball. I love sports. This is what I do. But if we’re going to get through this, we’re going to have to work together.”

***

Armstrong is pretty levelheaded about his stature in the basketball world. He feels fortunate to have experienced it on so many different levels. He’ll happily share his favorite Michael Jordan stories. He speaks with enthusiasm when discussing the work he does with his clients. While his career as an agent has certainly been lucrative, ultimately, the 22-year-old who just wanted to have an itinerary while he was on the road is in a position to give back to the sport that gave so much to him.

“I just consider myself a steward of the game,” Armstrong says. “I tried to play with honesty, and I always wanted to bring that same effort and energy whether I was an executive or representative.

“I’ve always tried to have that level of respect and be true to the game, and hopefully it will be true back to me.”

——————-