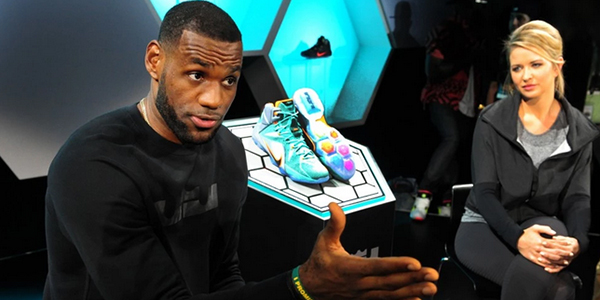

When the ball is tipped in Game 1, 28 players will have started alongside LeBron James in the NBA Finals.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, Fla. — This week, LeBron James will play in his 10th NBA Finals, a statistic that is both mind-boggling and insufficient, like saying Claude Monet created more than 2,000 paintings or Agatha Christie wrote at least 78 books. James has been the best player on all 10 of those Finals teams. He has made it to the Finals for five head coaches, four of whom never even made the playoffs without him. But maybe the stat that we should sip and swirl around our mouths, like a glass of fine wine, is this one:

When the ball is tipped in Game 1, 28 players will have started alongside LeBron James in the NBA Finals.

Twenty-eight. Some context: Nine players started alongside Michael Jordan in the Finals. Seventeen started alongside Kobe Bryant, 15 started alongside Tim Duncan and 19 started alongside Shaquille O’Neal. The statistics should not be used to reach a verdict in any best-ever debates. But they do tell the story of how James has dominated, and why he has won three titles instead of five or six.

The list of 28 includes some stars (Anthony Davis, Dwyane Wade, Chris Bosh, Kyrie Irving), but most of the 28 are remembered largely for playing with James.

For most of the 2015 Finals, while the Warriors started four possible Hall of Famers, James took the floor with Tristan Thompson, Timofey Mozgov, Iman Shumpert and Matthew Dellavedova. Only Shumpert ever started a playoff game without LeBron.

James’s Miami teams will forever be remembered for their Big Three of James, Wade and Bosh. But by the end of James’s fourth and final season in Miami, in 2014, the Heat lacked the depth of a champion. Thirty-four-year-old Rashard Lewis started five Finals games and Ray Allen started one; both would retire after that series.

Mario Chalmers started four Finals games in 2014 and ’17 overall alongside James—over four seasons. Chalmers burnished his collegiate reputation for hitting big shots, but big shots are a lot easier to hit when the defense is worried about LeBron James. Chalmers made 38.7% of his three-pointers in the four years he played with James and 31.8% in the other five years of his career.

The San Antonio Spurs beat James’s Heat in five games in those 2014 Finals. They did so largely by accepting that James would be the best player in the series. He led Miami in points (28.2), rebounds (7.8), assists and steals, and he shot efficiently: 57.1% from the field, including 51.9% from three-point land.

“If he is clicking on all cylinders, which he usually is in the playoffs, you’re not going to stop him,” said Danny Green, a Spurs starter in that series. “The key is to try to stop everyone around him, and try to limit those people.”

Green is one of “those people” now—he is expected to start alongside James for the Lakers. He has seen James’s greatness from the outside and the inside. LeBron James usually does not win the championship. But for a decade or more, the NBA has been his league.

At least twice in the past week, James answered questions about fellow Lakers star Anthony Davis with a flex: “That’s why I brought him here.” Players technically do not make trades. But he and Davis are good friends, they share an agent (Rich Paul of Klutch Sports) and last winter, James made it clear he wanted the Lakers to acquire Davis, who was starring but not winning in New Orleans.

In the offseason, Lakers general manager Rob Pelinka made the trade. It was the natural culmination of James’s power grabs, from “The Decision” in 2010 to now. There is a perception that James has an outsized influence in roster-building—because he does. But despite the hubris with which he began his tenure in Miami, and the perception that created, James has not been able to stack his team like an obnoxious Little League parent. In most of the years he made the Finals, his opponent had a deeper team.

To understand why he has done this, go back to when he didn’t do it. James spent his early years taking non-playoff rosters deep into the playoffs. In 2007, when he was 22, James started his first NBA Finals game—alongside Drew Gooden, Larry Hughes, Sasha Pavlovic and Zydrunas Ilgauskas. Ilgauskas was a very good player who made two All-Star teams. But that is not a starting five that belonged in the NBA Finals; James dragged it there.

Since then, James left Cleveland for a much better-run organization (Miami); returned home to Cleveland to finish some business; and then went to a Lakers team that had missed the playoffs for five straight seasons. There was no time to build rosters organically, and after seeing his Cavs mismanaged for the first seven years of his career, James took a more active role. He wanted Kevin Love instead of Andrew Wiggins, and Davis instead of Brandon Ingram and Lonzo Ball. In both cases, he got what he wanted—and was right to want it.

James knows what it is like to start NBA Finals games alongside Joel Anthony and an aging Mike Bibby. Anthony started all six Finals games in 2011, and Bibby started five, and of course when the Heat lost, James got blamed. (He did play poorly and tentatively in that series and deserved some of the criticism.) He has developed a formula for success. It generally involves James, ideally at least one other star, and then a cast of smart, defensive-minded players, (Shane Battier, Alex Caruso), shooters (Mike Miller, Ray Allen) and veterans who no longer care about their numbers (Richard Jefferson, Kevin Love).

James does not need exceptional talent around him to make the Finals, but he does need players who try to live up to his exceptional talent. This year, the Los Angeles Clippers brought a more talented team to the bubble, but they played without urgency. James’s teammates do not dare play that way.

Kentavious Caldwell-Pope did not win a playoff game in his first six NBA seasons. Now he is expected to start for the Lakers in the Finals. He has learned that playing with James is not about deferring to LeBron; it’s about meeting his expectations. Caldwell-Pope says James is “always quarterbacking the film sessions.” James has a photographic memory. Nobody wants to be in the wrong place in one of those snapshots.

“He remembers every guy’s cut, shot, missed or (made) shot, rebound, box-out, perfect assignment, good screen… he’s watching film, pointing out things on film that most people don’t see,” Green says. “I knew he was a smart guy and he thought the game through and had a pretty good memory. But you don’t realize it until you see him in a film session day in and day out. He’ll remember the plays that happened when we played them in 2019.”

James will try to win his fourth championship against the coach, Erik Spoelstra, who helped him win his first and second. Spoelstra had another observation of the James era: In LeBron’s Miami years, Spoelstra said, “The game started to change during that run and we had to adapt and adjust accordingly. You look at those games systematically and schematically and stylistically compared to where it is now, it’s two different sports.” The NBA has increased pace, emphasized spacing and three-point shooting, and moved away from post play. But two basketball truths have not changed: James is the best player in the world, and the guys who start alongside him are the luckiest.

——————-