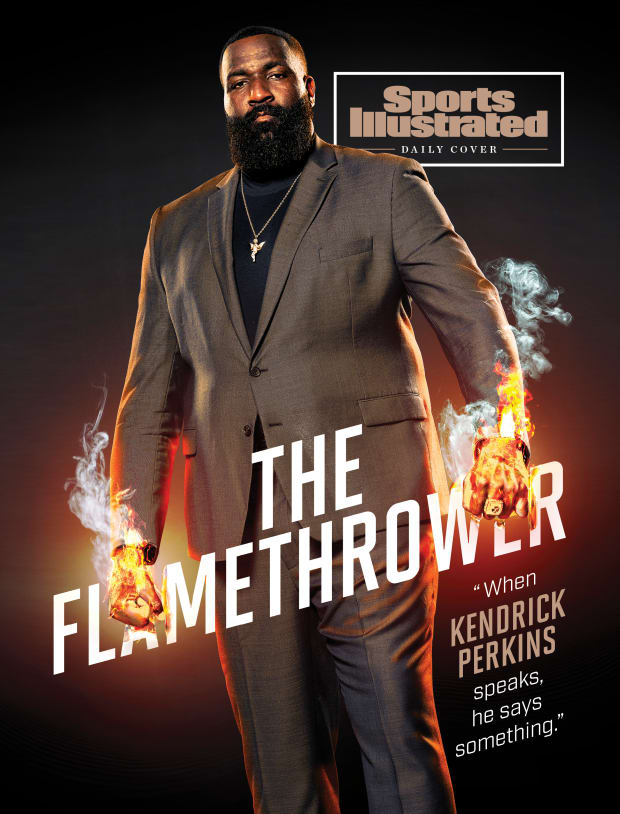

Known as a great teammate during his NBA career, Kendrick Perkins is sparing no one as a broadcaster.

“You can put this on the record,” Kendrick Perkins says at the end of an hourlong Zoom call that was, in fact, entirely on the record. It’s late September, days before the start of the NBA Finals, and Perkins is in his living room in Houston, ping-ponging from topic to topic. There’s the discipline LeBron James has when it comes to his body. “You know we were in a five-star steakhouse once,” says Perkins, James’s teammate for two seasons in Cleveland, “and he was getting treatment at the table?” There’s Kyrie Irving, whom Perkins criticized as a “distraction” for pushing back on the NBA’s plans to restart the season. “He’s not one of my leaders,” Perkins says. “I wouldn’t be following his lead.” There’s Kevin Durant, a once-close friend who Perkins has engaged in several social media scuffles. “I really don’t care if me and KD ever speak again in life,” Perkins says. “That really wouldn’t bother me.”

What Perkins wants on record—an opinion on the recently vanquished L.A. Clippers—is something he has said across ESPN platforms in his ubiquitous role with the network. As hot takes go, this one was lukewarm: “The Clippers, they was talking so much noise,” Perkins says. “The only person that really had the right to talk noise about championships was one guy, Kawhi [Leonard], and he didn’t say a word.” If Perkins thinks it, whether it’s Twitter, TV or a print interview, chances are he will find a way to say it. “And if you like it, you like it,” Perkins says. “If you don’t, sorry for your loss.”

That’s Perk: The man once hailed by SI.com as the NBA’s best teammate has become one of television’s fieriest flamethrowers. No subject is off limits, no topic will get anything but an unfiltered response. Irving’s attempt to get players to boycott the NBA’s restart? “If you took Kyrie Irving’s brain and put it in a bird … it’s going to fly backwards,” Perkins said on Get Up. Paul Pierce leaving LeBron James off his list of top-five players? Perkins popped on Hoop Streams to declare that Pierce, an ex-teammate, has disliked James his entire career. When Durant called Perkins a “sellout” for his criticism of Irving, Perkins, his voice quivering, delivered an emotional response on First Take.

“A lot of players who have recently left the game can have a hard time with divided loyalties,” says Rachel Nichols, whose show, The Jump, regularly features Perkins. “They don’t say anything too real. Perk is strong with his opinions. He says what he thinks.”

There’s an authenticity to Perkins. He makes mistakes. “I don’t think he’ll ever get Bam Adebayo’s name right,” says Brian Scalabrine, an ex-teammate. He isn’t trying to be polished. Perkins will make his point and—seemingly oblivious to the notion that he could be not talking and still on the air—adjust his mic, earpiece and whatever else is within reach. He has his favored expressions. If he thinks a team is finished, they are a “dead bird in the tall grass.” If he has a beef with someone, he’s “going to address you like numbers on a house.”

There’s a naturalness, though, too. Perkins understands the power of the anecdote. Ask Perkins about Kevin Garnett, and he won’t just tell you KG was a fiery competitor—he will reinforce it. He will recall a random Boston practice in 2008, when Leon Powe, a backup center, and Garnett went at it in practice. Powe, a recent second-round pick, starting squawking at Garnett.

“And KG was just like, ‘You know who you’re talking to? All right, I’m going to show you. I’m going to show you,’” Perkins says. “‘You’re talking to a great. I’ve won every motherf——g award you could ever motherf—–g imagine. Name it, motherf—-r, name it. Defensive Player of the Year? MVP?’ He started naming all his accolades and s—, and then all of a sudden he just turned it up a whole ’nother level.”

For big networks, there’s a formula for hiring analysts. Call it a pundit mold. Often, it’s a popular ex-player with an engaging personality. In 2019, Dwyane Wade was the hot commodity. He landed on the TNT desk. Last summer, it was Vince Carter. Sometimes it works: After some early bumps, Shaquille O’Neal has become a leading voice. Other times it doesn’t. Scottie Pippen fizzled out in his first go-round with ESPN after a few years of milquetoast takes. Shane Battier had a short career as an analyst. Magic Johnson’s was longer, and worse.

Perkins, though, is cut from a different cloth. A 14-year NBA career ended in 2018, with the 6′ 10″ center latching on with Cleveland for the Cavs’ final LeBron James–led playoff run. He never made an All-Star team, though he will remind an interviewer he flirted with a spot in 2010, when he averaged a career-best 10.1 points per game. He has a championship ring, won in 2008, when he was a screen-setting, defensive-minded tough guy in Boston, a role he continued over four-plus seasons in Oklahoma City.

Solid credentials … for something. “I always thought he would be a coach,” says Scalabrine. But an analyst? Was there room in TV’s glittery collection of articulate ex-All-Stars for a lumbering big man with a thick beard and a deep southern drawl? “If someone is high profile, it helps them get through the door,” says Gerry Matalon, a former ESPN talent exec who runs broadcasting workshops for the NBA Players Association. “Guys with a lower profile have to fight through the door.” Perkins has, emerging as a strong voice in a crowded industry. “The problem is too often we listen to how people talk and not what people say,” Scalabrine says. “Perk is very intelligent. When he speaks, he says something.”

***

Beaumont is a port city in southeast Texas, 30 miles from the Louisiana border. Kendrick Perkins grew up here, a gangly, oversized altar boy at Our Mother of Mercy Catholic Church, raised by his maternal grandparents in a two-bedroom farmhouse in Pear Orchard neighborhood, on Beaumont’s historically Black south side. His father, Kenneth, a basketball star at nearby Lamar University, took off to play professionally in New Zealand when Perkins was 18 months old. His mother, Ercell Minix, was shot and killed by her best friend when Perkins was five. His grandmother, Mary, was a housekeeper who took home $60 a week. His grandfather, Raymond, cleaned the local church for $350 a month. Social security checks helped the family survive. Many nights, Perkins says, he cried himself to sleep. For years, Perkins’s pursuit of an NBA career was fueled by the desire for his grandparents to live comfortably.

A standout center at Ozen High School, Perkins initially committed to Memphis, where John Calipari was rebuilding after a three-year stint coaching the New Jersey Nets. “Cal was authentic,” Perkins says. “He told me ‘I don’t want you here for 2 or 3 years. I want to make you a lottery pick after one year.’”

During his senior season at Ozen, Perkins noticed NBA scouts in the stands. Through Sonny Vaccaro, the basketball power broker who ran the prestigious ABCD Camp for high school prospects, Perkins arranged some NBA workouts in those pre-one-and-done days. Dallas, Houston and San Antonio brought Perkins in. Boston, too. After working out for the Celtics—“I destroyed Brian Cook,” Perkins said—Boston, with two first round picks in the 2003 draft, promised to take him, which it did with the 27th selection.

In high school, Perkins was a prolific scorer. “Jump hook, or I was dunking on you,” Perkins said. In Boston, Doc Rivers convinced Perkins to reinvent himself. Focus on defense, screen-setting and rebounding, Rivers said, and you will have a long career.

In Oklahoma City, Perkins began contemplating a post-NBA career. Coaching was his first choice. Thunder coach Scott Brooks often let Perkins speak up in team meetings and film sessions. “Honesty was always Perk’s priority,” Brooks says. “He was honest with his star players, he was honest with me, he was honest with himself.”

It often rankled Perkins how few big men were in the NBA head coaching ranks. “Point guards and small forwards are not the only ones who know the game,” Perkins says. “I wanted to break that mold.”

Back then, a media role never occurred to him. Perkins didn’t mind the media, even when it got intense. “It’s what you signed up for,” Perkins shrugs. “KG told me and [Rajon] Rondo, ‘Just like you ready to run to social media, ready to run to go read these newspaper articles about yourself when you have a good game, make sure you keep that same energy when you have a bad game.’” At times, he found it constructive. In 2012, after Oklahoma City fell behind 2–0 to San Antonio in the Western Conference finals, Perkins watched a replay of Game 2. He noted Steve Kerr, then an analyst for TNT, criticizing Perkins’s defense and suggesting Brooks pull him from the lineup. The Thunder adjusted, switching more pick-and-rolls, and went on to win four straight. During one of those games, Perkins forced Manu Ginobili into a turnover. At the next timeout, Perkins walked by the broadcast table and barked, “Say something about that tomorrow.”

“But I never took it personal,” Perkins says. “So anytime people in the media used to talk bad about me, I probably deserved it and I just took it on the chin.”

Perkins admired one media member: Charles Barkley. Too often, Perkins says, he would watch ex-players sound inauthentic. “Why were they trying to be like Stephen A. Smith?” Perkins wondered. Not Barkley. In Barkley, Perkins saw a kindred spirit, a southern-raised big man who was more substance than style. “You might not agree with a lot of things Chuck has said, but at least you can tell it’s coming from an honest and authentic place,” Perkins says. “He’s up there, he mispronounces words, sometimes he forgets names, but he’s being himself. That’s what makes him so good. He ain’t trying to be nobody else.”

In 2018, Perkins’s NBA clock ran out. He stuck with the Cavs through the Finals—final playoff stat line: zero minutes, two on-court altercations (one with Stephen Curry, the other with Drake)—and hoped to get another call. It never came. He got a few nibbles from overseas, but didn’t want to uproot his wife, Vanity, and their kids. “It was,” says Perkins, “a forced retirement.”

Last year, Perkins began to consider his options. There was coaching. In May, Perkins popped into the NBA draft combine. “Just to get my foot in the door,” Perkins said. Oklahoma City offered him a coaching job. Minnesota, too. By that point, though, Perkins had found a new passion: Twitter. Up until 2019, his Twitter account consisted of deep insights like, That was a great win and Stay with it and Thunder Up! He even deactivated it for a while. Perkins decided to do more. During the ’19 playoffs, he criticized the Celtics’ defense against the corner three. He woke up the next morning to a flood of replies.

He kept tweeting. His kicker, Carry on—is a nod to his followers to “not worry about what Big Perk is saying—just carry on with your day.” His follower count, up to nearly 300,000 today, kept growing.

Media inquiries started to trickle in. Perkins has always been an engaging interview. One of the NBA’s nastiest rivalries is between Rondo and Chris Paul. The two have clashed repeatedly, with an on-court brawl breaking out between the two in 2018. A decade earlier, Rondo-Paul was a simmering feud that, Perkins says, traces back to Rondo’s chafing at trade rumors involving the two. Maybe. Perkins, though, threw a match onto it. In 2009, days before Boston was scheduled to play Paul’s Hornets, Perkins was asked a benign question about the point guard matchup. His response: “Rondo thinks Chris Paul has the stats that he has because he has the ball in his hands all game.” Paul and Rondo had an altercation after that game—and have been battling ever since.

Podcasts came first. Radio requests, too. National, local—it didn’t matter. Perkins said yes to all of them. In one week, Perkins estimated he did 87 interviews. “Anybody that contacted me, I was ready,” Perkins says. “I was ready to do it. Once I realized that I was loving the media and this is what I wanted to do, I didn’t pass up anything. I was just enjoying it because I could talk basketball all day. We could argue, just like being in the barbershop.”

TV requests followed. Again, Perkins did them all. He wasn’t getting paid, so he leapfrogged between ESPN and FS1, the Lakers and Celtics of network rivals, whenever needed. “I think I’m the only person to do First Take and Undisputed in the same day,” Perkins says. By October, ESPN had seen enough. The network signed Perkins to a two-year deal—with the agreement he wouldn’t appear on any other national network. “I mean, I’m watching the games anyway,” Perkins said. “Why not talk about them on television?”

***

On most topics, Perkins prefers to shoot from the hip. “The guys who are former players who go up there and are afraid to tell the truth, or are afraid to speak their mind or call it like they see it,” says Perkins, “they don’t last long.” On bigger subjects, though, Perkins taps his inner circle. That’s Richard Gray, his former agent. Brandon Chappell, an assistant coach at Lamar. Rashad Phillips, whom Perkins calls “my big brother.” The group has periodic Zoom calls to discuss meatier topics. In June, there was one.

Perkins’s critiques of Irving ruffled feathers, none more than Durant’s, Irving’s close friend. Once airtight—Durant singled Perkins out in his MVP acceptance speech in 2014—the relationship had unraveled. Last January, Perkins tweeted that Russell Westbrook was the best player in Thunder history. As Perkins argued his point in his mentions—“Sometimes I like to start bar fights in the comments,” he concedes—Durant chimed in with a few of Perkins’s stats. Perkins responded by calling Durant’s decision to leave Oklahoma City for Golden State “the weakest move in NBA history.”

“It wasn’t nothing personal I was going at KD about,” Perkins says. “For him to try to come at me on Twitter, basically saying that I shouldn’t be able to talk basketball because I averaged two points, three rebounds. He knows what I brought to that Oklahoma City team. I’m not about to get all the way back and forth with it, but don’t act like I was just out there passing the ball either.”

When Perkins attacked Irving, Durant jumped back in, calling Perkins a sellout on Instagram. Perkins fumed. “I wanted to go for his neck,” Perkins says. He hopped on a Zoom with his people. They reminded him of the date: June 19—Juneteenth—the date commemorating the end of slavery in the U.S. Perkins cooled off. He went on TV the next day. He reminded Durant of Durant’s relationship with his kids. With his wife. Of Mother’s Day, 2011, when Durant and Perkins shared an emotional night on the road. He wiped away tears. It was perceived as sadness. It wasn’t.

“You don’t know how much it burned me up not to say what I wanted to say,” Perkins says. “I had to take the high road. People thought I was getting teary eyed because of our relationship. It wasn’t that at all. With everything going on in America, I had to hold back. But after I got through it, I was glad I did.”

Perkins says he has no relationship with Durant now. And that he doesn’t need one. “Think about this,” Perkins says. “I’m still cool with all my friends, everybody from the NBA family I still could call, I still go to dinner with, I still hang with, we still good people. They know I got a job to do. Except for one person. That’s Kevin Durant. So guess what? That tells me that I’m doing my job well and I’m staying loyal to my brotherhood. Especially the people that I know. Only sensitive guys get mad because you got to talk about them in the media.”

That, according to Perkins, would include Lou Williams. In July, Williams was excused from the NBA bubble to attend a funeral and was subsequently photographed at an Atlanta strip club. Williams said he was there to pick up food. Perkins said Williams needed to “do better.” Williams—on Twitter, of course—told Perkins to “shut up” and to “stop laughing and saying it’s just TV when you run into me.”

“That’s crazy because I ain’t never told Lou Will that,” Perkins says. “What would I get out of going up to Lou Will and telling him, ‘It’s just for TV,’ like I got something to be scared of Lou Will for? I said what I said and I say what I say. Nothing that I’m saying is just for TV. This is how I really feel about the game of basketball. Lou Will caused a distraction for the team. When you’re trying to win the championship, you don’t want no outside distractions. You’re trying to stay focused. That’s what the Lakers are doing right now. They’re locked in, but they got great leadership. I’m talking about, in-house, the Clippers lack leadership in their locker room.”

It doesn’t bother Perkins. Little does. There will always be a new topic to weigh in on. Last week, he went after Irving again, saying Irving was jealous of James. He called Pippen’s diminishing of a bubble championship disrespectful. He declared Rondo had punched his ticket to the Hall of Fame. He says he would never give up confidential information, but there isn’t a topic he would pass on wading into. “I am an analyst, and that’s my new career right now,” Perkins says. “I’ve got to critique what I see on television, and that’s how I got to go about it. There’s no hard feelings with nobody. I’m going to be this country boy, and I’m going to keep bringing this energy that I bring in doing my job. Ain’t nobody going to change that.”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here.

——————-