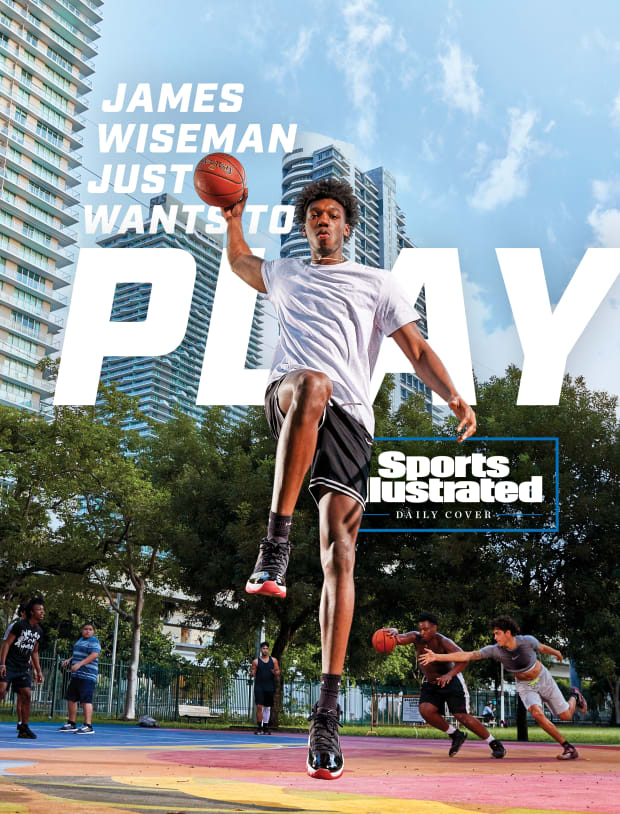

A potential top pick in the NBA draft, he tantalized at Memphis before the NCAA benched him. But what type of pro will he be?

The most important moments of James Wiseman’s day come just after his eyes open, when he climbs out of bed, fires up YouTube and just . . . breathes.

For the last year meditation has been a part of his daily routine. Kobe Bryant meditated, and Wiseman absorbs everything about the late Lakers star, from watching his online interviews to reading his Wizenard Series of children’s books. For 10 minutes, maybe 20, Wiseman will let his problems dissolve into low-frequency music. He will forget about the hardships of growing up in a modest house in Nashville, where food could be scarce and a good week was when the lights stayed on. Wiseman’s mother, Donzaleigh Artis, had a saying in that house: Just make it to Friday, to payday, when Artis, a school bus driver, would collect a check that would sustain them for another week.

He will forget about Memphis, about a once-promising college experience that ended almost before it started. Last fall Wiseman, a 7′ 1″ spring-loaded center, was a five-star recruit who shunned offers from NBA factories like Kentucky and Kansas to sign with the Tigers, coached by local legend—and four-time All-Star point guard—Anfernee Hardaway. But before Wiseman could suit up, the NCAA deemed him ineligible, kicking off a months-long legal fight that ended with his playing three games before withdrawing from school in mid-December. It was an ordeal, Artis says, “that took away his love for basketball. . . . I could see it in him. It felt like his world was crumbling.”

He will forget, at least momentarily, about what’s next: the NBA draft, scheduled for Nov. 18, when the 19-year-old Wiseman will likely be a top-five pick. For months he has been training at the Miami Hoop School, working out three times a day, packing muscle onto his 250-pound frame, extending his range to fit the mold of the modern NBA center. He’s eager for draft day, if only to formally close one chapter and begin a new one that is just about the game. “I wanted to embrace college with my teammates, win a national championship, have fun, live out the dream,” says Wiseman. “But you know how life is. Life happens. This year, though—it’s been kind of crazy.”

***

There are familiar notes to Wiseman’s story: Inner-city kid with a basketball addiction grows tall, draws the attention of top prep coaches and—poof!—becomes a prized recruit. Wiseman was a familiar figure in the Village Trail section of Nashville, banging in shots at all hours, often under the glow of streetlights. His sister, Jaquarius, seven years older, was a frequent one-on-one partner, as were the handful of cousins who lived nearby. His parents separated, but his father, Stefan, worked two jobs to help the family make ends meet.

Wiseman loved basketball. He just didn’t always like the physicality of it. As a four-year-old he was allowed to play with fourth-graders, because of his height; in church league games, an oversize Wiseman would stand in the corner, arms crossed above his head. “He didn’t want anyone to touch him,” Artis recalls. She signed him up to play football in elementary school. He got used to contact quickly and was ready to bang on the court. By eighth grade Wiseman had shot up to 6′ 8″. From then on, it was basketball only. He started showing up at a neighborhood court, a skinny 13-year-old angling to get in games with men in their mid-20s. “They used to rough me up,” says Wiseman. “But that’s how I gained my mental toughness.”

Where Wiseman’s story deviates is in high school. As a freshman, he enrolled at the private Ensworth School, then a basketball powerhouse. He scored 10.0 points per game that year, and Tennessee quickly offered him a scholarship. After two years he and his mom moved across the state so that he could transfer to public Memphis East High. The coach: Penny Hardaway.

To understand Hardaway’s stature in Tennessee, think Larry Bird in Indiana or Michael Jordan in North Carolina. Hardaway’s image greets travelers at the Memphis airport. Wiseman grew up with Penny in a Magic uniform as his screen saver. He coveted Hardaway’s playmaking skills, skills Hardaway soon drilled into him. “The modern-day big has to play-make and put the ball on the floor,” Wiseman says. “He really trained me as a guard.”

Wiseman’s decision to transfer attracted the attention of the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association. A few months earlier he had joined Team Penny, the Hardaway-sponsored AAU team. In November 2017, the TSSAA declared Wiseman and his teammate Ryan Boyce ineligible for the ’17–18 season, citing a rule that athletes who transfer to a high school are ineligible if during the previous 12 months they have had any link to their new coach—such as playing for his AAU team. A temporary restraining order allowed Wiseman and Boyce to suit up. Wiseman averaged 18.5 points that season and led East High to the Class AAA state championship. Three days after the state title game, Memphis hired Hardaway.

In November ’18, Wiseman committed to play for the Tigers—and then the NCAA got involved. Initially, it cleared Wiseman. But in the summer of 2019 the association began looking more deeply at Wiseman’s relationship with Hardaway, specifically the $11,500 Hardaway gave Artis to cover her family’s move from Nashville to Memphis when her son transferred high schools. The issue wasn’t that Hardaway had since become the coach at Memphis; it was that he was a booster of the school. In 2008 he had donated $1 million to help fund the Penny Hardaway Athletics Hall of Fame. Boosters aren’t allowed to provide money to recruits or their families; by helping Wiseman’s family, Hardaway had jeopardized his eligibility.

“None of this was ever James’s fault,” Artis says. “My daughter [Jaquarius] went to the University of Memphis. She had gotten real depressed. She had looked into coming home. She wanted to transfer, but there was an issue with her credits. So I thought, ‘How do I help both my kids?’ I could move to Memphis. My daughter could go back to school. My son could go play for Penny. But it was really about my daughter.

“James knew nothing about it. You think $11,500 is money for the No. 1 player? That was way before James even thought about Memphis. How did Penny ever know he was going to be the coach at Memphis? I left my job to go help my kids. I had been at my job for almost 15 years.”

Hardaway expresses similar frustration, noting that he never recruited Wiseman to East High. “There’s no rule against this kid wanting to relocate,” says Hardaway. “And then if he relocates, he can say, ‘I want to play for a guy who played the game at the highest level.’ ” The idea that there was a grand plan for Wiseman to end up playing for him in college, says Hardaway, is nonsense: “I was never planning on being the Tigers’ coach. It just happened. If I was really trying to keep James Wiseman, I would have stayed at East High School [instead of taking the Tigers job] and been like, Give me one more year, [hire] an interim coach, and then I’m going to come [to Memphis] and then I’m going to bring James. That’s not how it happened.”

To Artis, family has a deeper meaning. Before James was born, she lost her five-year-old son, Bobby Ray, in an accidental drowning. “It never goes away,” Artis says. “It never gets better.” She swore if God ever blessed her with another son, “I won’t mess it up.” Tattooed to her wrist is #3Strong4Life. The three is for her living family; the four is for what the family will be “someday, when we all get to heaven.” Jaquarius has the same tattoo.

On Nov. 5, Wiseman made his Tigers debut, notching 28 points and 11 boards against South Carolina State. That same day, though, the NCAA informed Memphis he was likely ineligible. Three days later Wiseman sued, seeking—and receiving—a temporary restraining order that allowed him to play. He’d play the next two games, bringing his averages to 19.7 points, 10.3 rebounds and 3.0 blocks in 23 minutes per game. On Nov. 14, Wiseman dropped his lawsuit against the NCAA and Memphis then declared him ineligible, a precursor to immediately applying for his reinstatement as part of an expected settlement with the NCAA. A week later, though, the NCAA suspended Wiseman for 12 games and ordered him to donate $11,500 to a charity of his choice. Everyone from former NBA star Reggie Miller to then Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang ripped the ruling. ESPN analyst Jay Williams promoted a GoFundMe for Wiseman to pay the fine.

“James is the nicest kid. He didn’t deserve any of that,” Hardaway says. “I gave a million dollars of my own money to the school out of the kindness of my heart, and I got penalized for it. And then James got penalized for it. That’s really weird to me.”

Wiseman had a choice. He could serve his suspension and rejoin the Tigers in mid-January, in time for the American Athletic Conference tourney. He had remained eligible; he says he had a 4.0 GPA in his first semester. Always a dedicated student, he speaks conversational Mandarin and has dreams of becoming a venture capitalist. Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich is one of his favorite books. He keeps a journal of the philanthropic things he hopes to do, like opening a community center.

But the ongoing drama surrounding his playing status had drained him. “He was falling apart,” Artis says. “If [the NCAA] was going to punish anyone, it should have been me and Penny.” On Dec. 19, Wiseman withdrew from college. “It was just overwhelming,” says Hardaway. “I get the NCAA has to do a job to do. But he was like, Hey man, I haven’t done anything. Why am I being punished?”

***

Here’s the thing about the NBA: Teams don’t care about NCAA rules. At all. “Totally irrelevant,” says Ryan McDonough, the former GM of the Suns. In 2018, Deandre Ayton, a freshman center at Arizona, was caught up in a recruiting scandal. His coach, Sean Miller, was overheard on FBI wiretaps discussing paying him “$10,000 a month” (Miller has denied wrongdoing). Ayton left school that spring. McDonough took him with the No. 1 pick.

They care about Wiseman’s size. Basketball has evolved, but the center position is still valuable. Gone are the days of post-up pivots; the 76ers, with Joel Embiid, are one of the few teams that play through a traditional five. In are springy, versatile big men who can protect the paint, run the floor and rim-roll off picks to throw down lobs—the Heat’s Bam Adebayo, for example, or the Hawks’ Clint Capela. If a big can also space the floor by shooting threes, à la Anthony Davis, then he’s what every team is seeking.

Wiseman is chiseled from that rim-runner mold. “He’s a f—— giant,” says an NBA scout. “He’s as big and athletic as anybody in our league. And a mobile 7-footer who can dunk and rebound? At worst, this kid is going to be a starter.” And, Hardaway notes, “He’ll protect the rim, too.”

But can Wiseman add the offensive game and long-distance shooting that could turn him into an All-Star? He has studied fellow lefty David Robinson, with his agility and touch. (Centers may not have hoisted threes in Robinson’s time, but the Admiral commanded from midrange.) “Back then, there weren’t a lot of big men that could shoot,” Wiseman says. “He changed the game.”

In high school Hardaway also began to change Wiseman’s jump shot, moving the release point from behind his head to closer to the front of it for a quicker and more accurate trigger. “That really took his range further out,” says Hardaway. “He was always striving to be better.” With so little game experience, it’s hard to know whether Wiseman will be a reliable marksman, but the mechanics are now there.

Hardaway would also show him film of Shaquille O’Neal. Not late-career Shaq, when he was more of a stationary presence. But early, Orlando Shaq, who ran the floor like a forward. “He told me that was how I was going to get a lot of my buckets,” Wiseman says.

Wiseman wants his game to span generations, so during the pandemic he doubled down on his own film work, particularly of 1980s Moses Malone and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He studied the ’85 Finals to watch Abdul-Jabbar battle with Kevin McHale and Robert Parish. “I looked at the whole series, really,” Wiseman says. “The concepts, how they ran their plays, all aspects.”

He also studied Kobe. Wiseman never met Bryant; they crossed paths once at a camp when Wiseman was in high school. But he revered Bryant’s approach. He devoured his books, a Harry Potter–meets-Hoosiers series conceived by Bryant with a Phil Jackson–esque lead character, Rolabi, who helps players discover their strengths. “If you have ups and downs or struggles, you have got to be willing to have perseverance, to not being afraid to fail, to always just keep working,” Wiseman says. “There was a lot of great advice that came from that book.”

Any lingering questions about Wiseman boil down to what scouts and executives haven’t seen from him: a consistent motor. “He drifted through games at times,” says a Western Conference team executive. And fair or not, Wiseman’s decision to bail out of college raised doubts about his mental toughness for at least some. “The big questions I have are, ‘Does he really want to hoop? Does he really care?’ ” says an exec from a lottery team. “He’s got all the tools to be great. He just has to want it.”

Hardaway is sure Wiseman does: “He’s definitely mentally tough. He understands the grind, he understands what he needs to do.” The Memphis experience behind him, Wiseman’s love for the game has been restored. His family sees that. When Wiseman pops back into Nashville to visit, Artis has to make sure there is a gym open and available to him. “You can see it in the smile on his face,” says Artis. “He eats, drinks and sleeps basketball now. When we talk on the phone, he starts by telling me what his shot looks like. He’s happy again.”

As for where he’ll play, Wiseman, predictably, says he doesn’t care. The Timberwolves, with the top pick, could plant him next to 6′ 11″ All-Star Karl-Anthony Towns in a dynamic frontcourt. He’s had virtual interviews with the Warriors, who select at No. 2. “I want to be No. 1,” says Wiseman. “But, honestly—it’s all about the best fit.”

Wiseman just wants to play. Three games at Memphis, and then you have to go back to high school and the McDonald’s All-American game to find his last real competition. With the starting date of the next NBA season murky, he could go two years between full competitive campaigns. All he can do in the meantime is breathe deep and wait.

“I miss it, man,” Wiseman says. “I miss it a lot. Everything about this last year has been really hard. I’m ready to put it all behind me. I’m ready to move forward.”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here.

——————-